“FAITHS IN SUFFOLK”. |

JAINS |

LINKS TO LIST OF ARTICLES ABOUT AND BY JAINS |

|

Mahavira’s admonition to his Chief Disciple Indrabhuti Gautama. |

IMAGINE YOU ARE A JAIN |

|

Your religion recognises Jinas (or Tirthankaras), |

|

Some of your earliest writings were composed |

|

You do not believe in a creator God, |

|

Your

belief in Karma |

|

You

respect all forms of life, |

|

Some

Jains follow a vegan diet |

|

Fasting is an important part of your religion. |

|

You may worship in your home, in hall or temple. |

|

You also meditate and make confession. |

|

You honour

truthfulness, faithfulness |

|

- |

|

|

|

Taken from the Jain Faith Card in the Diversity Game |

|

* |

THE JAINS |

|

Souls render

service to one another |

|

I grant

forgiveness to all living beings |

|

Jainism preaches friendship with all living things. Its aim is the welfare of the whole universe, not only human beings. Jain philosophy emphasises that animals and plants have souls, and even the elements of earth, air fire and water are made up of tiny souls. All contain life, and therefore are not to be violated and exploited by humanity, but to be treated as our benevolent friends. Violence towards our fellow human beings or towards other species is violence to the self. |

|

The Jain dictum parasparopagraho jivanam “souls render service to one another” offers an enduring alternative to the modern Darwinian formula of 1. survival of the fittest”. The fundamental Jain principle of ahimsa, non violence extends to all forms of life. It should be our firm conviction that amity between all humanity and all life is the true wealth of our planet. |

HISTORY OF JAINISM |

|

Jainism is one of the oldest living religions. The term Jain means the follower of the Jinas (Spiritual Victors), human teachers who attained omniscience. These teachers are also called Tirthankaras (Ford makers), those who help others escape the cycle of birth and death. It is believed that there have been twenty four Tirthankaras in the present cosmic cycle. |

|

The twenty fourth Tirthankara. Vardhamana, usually called Mahavira (the Great Hero), was born in 599 BCE into a ruling class family of what is now the Indian state of Bihar. At the age of thirty, he left home on a spiritual quest. After twelve years of trials and austerities he attained omniscience. Eleven men became his ganadharas, chief disciples, and during the next thirty years, it is thought that his followers grew to about 50,000 male and female ascetics and half a million lay people. At seventy two Mahavira died and attained nirvana, that blissful state beyond life and death. |

|

Jains do not believe that Mahavira was the founder of a new religion. He consolidated the faith by drawing together the teachings of the previous Tirthankaras, particularly those of his immediate predecessor, Parsva, who lived about 250 years earlier in Varanasi. |

|

Initially the followers of Jainism lived throughout the Ganges Valley. Around the time of Ashoka (250 BCE) most Jains migrated to the city of Mathura on the Yamuna River. Later, many travelled west to Rajasthan and Gujarat and south to Maharashtra and Karnataka where Jainism rapidly grew in popularity. |

JAIN PRACTICES |

|

Jains believe that to attain the higher stages of personal development or enlightenment, lay people must adhere to the five anuvratas (small vows). The vows taken by monks and nuns are the five mahavratas (great vows), a more rigorous interpretation of the vratas for the laity. These five vows are: |

|

1. Ahimsa (non violence). This is the fundamental vow from which all other vows stem. For lay people, it involves not killing or causing intentional harm. Jains are strictly vegetarians and many devout Jains observe further restriction on foods said to support large amounts of microscopic life such as figs, honey, alcohol and root vegetables. Ahimsa also prohibits Jains taking up occupations that harm humans or animals. |

|

2. Satya (truthfulness). This is enjoined in order to not harm another by speech. |

|

Asteya (not stealing). This is the principle of not taking what belongs to another. Monks and nuns must only take what is specifically given, and :hen, only if it is in accord with monastic rules. |

|

1. Brahmacharya (chastity). For lay Jains, this means avoiding sexual promiscuity. For monks and nuns it is complete celibacy. |

|

4. Aparigraha (non materialism). For lay Jains, this means limiting their acquisition of material goods. For monks and nuns, ownership is extremely restricted. The monks of the Digambara sect do not even own clothes. |

|

In addition to these five vows, many Jains voluntarily undertake austerities (tapas) for a time such as eating only one meal a day or fasting. |

JAIN BELIEFS |

|

Anekantavada (non onesidedness). This philosophy states that no single perspective on an issue contains the whole truth. Substance, time, place and the conditions of the observer all effect the viewpoint, so any event should be considered from different points of view. Ideally, this should result in a non dogmatic approach to the doctrines of other faiths. |

|

Loka (the universe). According to Jain scriptures space is infinite but only a finite portion is occupied by what is known as the universe. Everything within this universe, whether sentient (jiva) or insentient (ajiva), is eternal, although the forms that a thing may take are transient. Human beings inhabit the middle of the universe, with the heavens above and hells below. Jains believe that this uncreated, eternal universe has always existed, so they do not believe in a creator god. |

|

jiva (Soul). Jains believe that all living beings have an individual soul (jiva) which occupies the body, a conglomerate of atoms. At the time of death, the soul leaves the body and immediately takes birth in another. Attaining moksha /nirvana and thereby ending this beginningless cycle of birth and death and death is the goal of Jain practice |

|

Ajiva (non soul). Ajiva is everything in the universe that is insentient, including matter, the media of motion and of rest, time and space. |

|

Karma. All jivas are equal in their potential for infinite knowledge, energy and bliss. However, during the soul’s beginningless embodied state, these innate qualities are obscured by different types of karma. Karma is understood as a form of subtle matter which adheres to the soul as a result of its actions of body, speech and mind. This accumulated karma is the cause of the soul’s bondage in the cycle of birth and death. The amounts and types of karmic particles bound to the soul determine the type of body which it inhabits. |

|

Moksha or nirvana (eternal liberation through enlightenment). The ultimate aim of life is to emancipate the soul from the cycle of birth and death. This is done by exhausting all bound karmas and preventing further accumulation. According to Jainism, one must be human to achieve this and must lead an ascetic life following the Jain principles. When the soul has progressed from its state of limited perception obscured by karma to its pure state of omniscient knowledge free of all karma, it rises to the summit of the universe where it exists forever. Such a soul is a Siddha, Perfected Being. |

|

To achieve moksha, it is necessary to have the following three qualities known as the Three jewels: |

|

1. Enlightened world view: belief in the essentials of Jainism. |

|

2. Enlightened knowledge: knowledge of the operation of karma and its relationship to the soul. |

|

3. Enlightened conduct: adherence to the five vows. |

JAIN SCRIPTURES |

|

The Jain canon contains some sixty texts and is divided into three main groups, the Purvas (old texts:12 books), the Angas (limbs: 12 books) and the Angabahya (subsidiary canon). Not all are extant. In addition to the three canon itself, there are extensive commentaries written in Sanskrit by the monk scholars. The Tattvartha Sutra, written in the second century CE, belongs to this group. This important text summarizes the entire Join doctrine and forms the basis for Jain education today. |

THE JAIN COMMUNITY |

|

Through the millennia, the Jain community has contributed enormously to the arts, politics and philosophy of India. Its most visible contribution in be seen in the nation’s sculpture and architecture. |

|

There are two main groups of ascetics in the Jain community Shvetambaras, and Digambaras. |

|

Shvetambara (white robed) monks and nuns wear three pieces of white clothing and carry a set of begging bowls, a whisk broom, a walking stick rid a blanket. A Shvetambara sub group called Sthanakvasis and a sub group of them called Terapanthis also wear a cloth over the mouth to avoid swallowing insects. |

|

Digambara monks renounce all property including clothes and begging bowls. They carry a peacock feather whisk broom and a gourd containing washing water. Digambara nuns wear a white sari. |

|

The terms Shvetambara, Sthanakvasi, Terapanthi and Digambara are also used to define the lay followers of these ascetics. There are approximately 7 million Jains in the world, about 100,000 of whom live outside India in North America, Britain, Belgium, East and South Africa, Indian Ocean Islands, South East Asia and Australia. |

|

23 November 1995 |

|

* |

JAINISM FOR THE MODERN WORLD |

|

The way of eternal truth |

|

Anger destroys goodwill, |

|

Jainism originated for the benefit of all beings. Its main aim is the welfare of the whole universe, not only of humanity. It teaches us to love and help one another for the benefit of all. it preaches friendship with all living things. This is the central theme governing Jain philosophy. |

|

Modern. science gave us a formula survival of the fittest. This formula, based on the idea of the struggle for existence, infers that you have to live at the cost of others. But true science, cannot exist for long without spirituality. Many scientists and thinkers have replaced the Darwinian formula with the theory of coexistence live and let others live. But while this second formula is interesting, it also lacks respect for life and allows one to evade reality: “I am not killing him. 1 allow him to live but, if he dies on his own, why should 1 bother?” This is escapism. |

|

That is why the sarvodaya approach of India corrected this second formula to say Live to let live. You are a human being; you should live in a way that helps others to live. This dictum is not new to Indian civilization. Mahavira, the twenty fourth Tirthankara, gave this mantra 1600 years ago. Furthermore, when Mahavira said “Live to let others live”, he was not only referring to human beings; he was speaking for all life, including animals, earth, water, fire, air and trees. All are living elements and all serve humanity. We should honour this debt, this obligation. |

|

Nature and its cycle (of cause and effect) are integral to the sustenance and protection of thisearth. The elements of nature are not just useful materials for us, but living beings who should be treated as beneficent friends. The present state of Mother Earth as spoiled and deformed is the reflection of our own mind. The moot question is why humanity should kill other living things; why should we hate and neglect our fellow beings? It should be our firm conviction that amity between all humanity and all life is the real wealth. Non violence is the only way to revolutionise humanity. Only through nonviolence can we survive. When humans despoil (pollute) nature, we pollute the very environment we need in order to live, we issue an open invitation for our own destruction. |

|

It is high time we turned back from the path of unlimited and thoughtless misuse of nature which is destroying Mother Earth. Self imposed restraint is the call of the day for the bright future of humanity. It can only be achieved if we adopt a policy of invest more, use less. |

|

The philosophy of Tirthankara Mahavira goes beyond the principles of modern science. It teaches us to live a life that allows all the elements of nature to remain in peace and harmony, without fear. Fearlessness is the foundation of supreme truth. It is rooted in nonviolence. |

|

Pujya

Shris Sheelchandravijayji & |

QUOTES FROM JAIN SCRIPTURES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quotations from Uttradhyayana Sutra |

|

* |

MAHAVIRA’S ADMONITION TO HIS CHIEF DISCIPLE INDRABHUTI GAUTAMA. |

|

As the fallow leaf of the tree falls to the ground when its days

are gone, even so the lives of men (come to a close). Gautama. be careful all

the while. |

|

A rare chance in the long course of time |

|

Though one believes in the law, |

|

When your body grows old, |

|

Cast aside all your attachments |

|

Leave your friends and relations, |

|

Now you have entered the path cleared of thorns, |

|

You have crossed the great ocean, |

|

Going through the same religious practices as perfected saints, you

will reach the world of perfection, Gautama, where there is safety and

perfect happiness |

|

[Ven.Sudharma then said:] |

|

Uttaradhyayana

Sutra |

|

* |

JAIN DECLARATION ON NATURE |

|

In 1990, in consultation with all Jain communities internationally,IoJ initiated the preparation of Jain Declaration on Nature (JDoN).It defines the essential Jain values, and the concepts of nature,ecology and the environment. Some 30 eminent Jain scholars were involved in drafting the JDoN, with final editing by Dr L M Singhvi. The two largest Jain communities in the UK, namely Oshwal Association of the UK and Navnat Vanik Association of the UK, had the opportunity of working together on this project.This document was officially presented to the President of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), HRH Prince Philip, on 23 October 1990 at Buckingham Palace in a ceremony that was attended by 21 leaders representing Jain communities from all over the world. This marked the official entry of the Jain community into the WWF Network on Conservation and Religion, making Jainism the eighth faith to be represented in this organisation. This was an occasion about which every Jain can take pride because Jains throughout the world had worked together to promote a common cause. |

|

The Jain Declaration on Nature The Jain tradition which enthroned the philosophy of ecological harmony and non violence as its lodestar flourished for centuries side by side with other schools of thought in ancient India. It formed a vital part of the mainstream of ancient Indian life, contributing greatly to its philosophical, artistic and political heritage. During certain periods of Indian history, many ruling elites as well as large sections of the population were Jains, followers of the Jinas (Spiritual Victors).The ecological philosophy of Jainism which flows from its spiritual quest has always been central to its ethics, aesthetics, art, literature, economics and politics. It is represented in all its glory by the 24 Jinas or Tirthankaras (Path finders) of this era whose example and teachings have been its living legacy through the millennia. |

|

Although the ten million Jains estimated to live in modern India constitute a tiny fraction of its population, the message and motifs of the Jain perspective, its reverence for life in all forms, its commitment to the progress of human civilization and to the preservation of the natural environment continues to have a profound and pervasive influence on Indian life and outlook. |

|

In the twentieth century, the most vibrant and illustrious example of Jain influence was that of Mahatma Gandhi, acclaimed as the Father of the Nation. Gandhi’s friend, Shrimad Rajchandra, was a Jain. The two great men corresponded, until Rajchandra’s death, on issues of faith and ethics. The central Jain teaching of ahimsa (non violence) was the guiding principle of Gandhi’s civil disobedience in the cause of freedom and social equality. His ecological philosophy found apt expression in his observation that the greatest work of humanity could not match the smallest wonder of nature. |

I THE JAIN TEACHINGS |

|

1. Ahimsa (non violence) |

|

The Jain ecological philosophy is virtually synonymous with the principle of ahimsa (non violence) which runs through the Jain tradition like a golden thread. |

|

“Ahimsa parmo dharmah” (Non violence is the supreme religion). |

|

Mahavira, the 24th and last Tirthankara (Path finder) of this era, who lived 2500 years ago in north India consolidated the basic Jain teachings of peace, harmony and renunciation taught two centuries earlier by the Tirthankara Parshva, and for thousands of years previously by the 22 other Tirthankaras of this era, beginning with Adinatha Rishabha. Mahavira threw new light on the perennial quest of the soul with the truth and discipline of ahimsa. He said: |

|

“There is nothing so small and subtle as the atom nor any element so vast as space. Similarly, there is no quality of soul more subtle than non violence and no virtue of spirit greater than reverence for life.” |

|

Ahimsa is a principle that Jains teach and practise not only towards human beings but towards all nature. It is an unequivocal teaching that is at once ancient and contemporary. The scriptures tell us: |

|

“All the Arhats (Venerable Ones) of the past, present and future discourse, counsel, proclaim, propound and prescribe thus in unison: Do not injure, abuse, oppress, enslave, insult, torment, torture or kill any creature or living being.” |

|

In this strife torn world of hatred and hostilities, aggression and aggrandisement, and of unscrupulous and unbridled exploitation and consumerism, the Jain perspective finds the evil of violence writ large. |

|

The teaching of ahimsa refers not only to wars and visible physical acts of violence but to violence in the hearts and minds of human beings, their lack of concern and compassion for their fellow humans and for the natural world. Ancient Jain texts explain that violence (himsa) is not defined by actual harm, for this may be unintentional. It is the intention to harm, the absence of compassion, that makes action violent. Without violent thought there could be no violent actions. When violence enters our thoughts, we remember Tirthankara Mahavira’s words: |

|

“You are that which you intend to hit, injure, insult, torment, persecute, torture, enslave or kill.” |

|

2. Parasparopagraho jivanam (interdependence) |

|

Mahavira

proclaimed a profound truth for all times to come when he said: |

|

Jain cosmology recognises the fundamental natural phenomenon of symbiosis or mutual dependence, which forms the basis of the modern day science of ecology. It is relevant to recall that the term ‘ecology’ was coined in the latter half of the nineteenth century from the Greek word oikos, meaning ‘home’, a place to which one returns. Ecology is the branch of biology which deals with the relationships of organisms to their surroundings and to other organisms. |

|

The ancient Jain scriptural aphorism Parasparopagraho jivanam (All life is bound together by mutual support and interdependence) is refreshingly contemporary in its premise and perspective. It defines the scope of modern ecology while extending it further to a more spacious ‘home’. It means that all aspects of nature belong together and are bound in a physical as well as a metaphysical relationship. Life is viewed as a gift of togetherness, accommodation and assistance in a universe teeming with interdependent constituents. |

|

3. Anekantavada (the doctrine of manifold aspects) |

|

The concept of universal interdependence underpins the Jain theory of knowledge, known as Anekantavada or the doctrine of manifold aspects. Anekantavada describes the world as a multifaceted, ever-changing reality with an infinity of viewpoints depending on the time, place, nature and state of the one who is the viewer and that which is viewed. |

|

This leads to the doctrine of syadvada or relativity, which states that truth is, relative to different viewpoints (nayas). What is true from one point of view is open to question from another. Absolute truth cannot be grasped from any particular viewpoint alone because absolute truth is the sum total of all the different viewpoints that make up the universe. |

|

Because it is rooted in the doctrines of Anekantavada and syadvada, Jainism does not look upon the universe from an anthropocentric, ethnocentric or egocentric viewpoint. It takes into account the viewpoints of other species, other communities and nations and other human beings. |

|

4. Madhyastata (equanimity) |

|

The discipline of non violence, the recognition of universal interdependence and the logic of the doctrine of manifold aspects, leads inexorably to the avoidance of dogmatic, intolerant, inflexible, aggressive, harmful and unilateral attitudes towards the world around. It inspires the personal quest of every Jain for Madhyastata (equanimity) towards both jiva (animate beings) and ajiva (inanimate substances and objects). It encourages an attitude of give and take and of live and let live. It offers a pragmatic peace plan based, not on the domination of nature, nations or other people, but on an equanimity of mind devoted to the preservation of the balance of the universe. |

|

5. Jiva daya (compassion, empathy and charity) |

|

Although the term ‘ahimsa’ is stated in the negative (a=non, himsa=violence), it is rooted in a host of positive aims and actions which have great relevance to contemporary environmental concerns. |

|

Ahimsa is an aspect of daya (compassion, empathy and charity), described by a great Jain teacher as “the beneficent mother of all beings” and “the elixir for those who wander in suffering through the ocean of successive rebirths.” |

|

Jiva-daya means caring for and sharing with all living beings, tending, protecting and serving them. It entails universal friendliness (maitri), universal forgiveness (kshama) and universal fearlessness (abhaya). |

|

Jains, whether monks, nuns or householders, therefore, affirm prayerfully and sincerely, that their heart is filled with forgiveness for all living beings and that they have sought and received the forgiveness of all beings, that they crave the friendship of all beings, that all beings give them their friendship and that there is not the slightest feeling of alienation or enmity in their heart for anyone or anything. They also pray that forgiveness and friendliness may reign throughout the world and that all living beings may cherish each other. |

II JAIN COSMOLOGY |

|

Jains do not acknowledge an intelligent first cause as the creator of the universe. The Jain theory is that the universe has no beginning or end. It is traced to Jiva and Ajiva, the two everlasting, uncreated, independent and co existing categories. Consciousness is jiva. That which has no consciousness is ajiva. |

|

There are five substances of ajiva: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pudgala (matter) has form and consists of individual atoms |

|

The Jiva (soul) has no form but, during its worldly career, it is vested with a body and becomes subject to an inflow of karmic ‘dust’ (asravas). These are the subtle material particles that are drawn to a soul because of its worldly activities. The asravas bind the soul to the physical world until they have brought about the karmic result when they fall away ‘like ripe fruit’ by which time other actions have drawn more asravas to the soul. |

|

With the exception of the Arihantas (the Ever Perfect) and the Siddhas (the Liberated), who have dispelled the passions which provide the ‘glue’ for the asravas, all souls are in karmic bondage to the universe. They go through a continuous cycle of death and rebirth in a personal evolution that can lead at last to moksha (eternal release). In this cycle there are countless souls at different stages of their personal evolution: earth-bodies, water bodies, fire bodies, air bodies, vegetable bodies, and mobile bodies ranging from bacteria, insects, worms, birds and larger animals to human beings, infernal beings and celestial beings. |

|

The Jain evolutionary theory is based on a grading of the physical bodies containing souls according to the degree of sensory perception. All souls are equal but are bound by varying amounts of asravas (karmic particles) which is reflected in the type of body they inhabit. The lowest form of physical body has only the sense of touch. Trees and vegetation have the sense of touch and are therefore able to experience pleasure and pain, and have souls. Mahavira taught that only the one who understood the grave demerit and detriment caused by destruction of plants and trees understood the meaning and merit of reverence for nature. Even metals and stones might have life in them and should not be dealt with recklessly. |

|

Above the single sense jivas are micro organisms and small animals with two, three or four senses. Higher in the order are the jivas with five senses. The highest grade of animals and human beings also possess rationality and intuition (manas). As a highly evolved form of life, human beings have a great moral responsibility in their mutual dealings and in their relationship with the rest of the universe. |

|

It is this conception of life and its eternal coherence, in which human beings have an inescapable ethical responsibility, that made the jam tradition a cradle for the creed of environmental protection and harmony. |

III. THE JAIN CODE OF CONDUCT |

|

1. The five vratas (vows) |

|

The five vratas (vows) in the Jain code of conduct are: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The vow of ahimsa is the first and pivotal vow. The other vows may be viewed as aspects of ahimsa which together form an integrated code of conduct in the individual’s quest for equanimity and the three jewels (ratna traya) of right faith, right knowledge and right conduct. |

|

The vows are undertaken at an austere and exacting level by the monks and nuns and are then called maha vratas (great vows). They are undertaken at a more moderate and flexible level by householders and called the anu vratas (‘atomic’ or basic vows). |

|

Underlying the Jain code of conduct is the emphatic assertion of individual responsibility towards one and all. Indeed, the entire universe is the forum of one’s own conscience. The code is profoundly ecological in its secular thrust and its practical consequences. |

|

2. Kindness to animals |

|

The transgressions against the vow of non violence include all forms of cruelty to animals and human beings. Many centuries ago, Jains condemned as evil the common practice of animal sacrifice to the gods. It is generally forbidden to keep animals in captivity, to whip, mutilate or overload them or to deprive them of adequate food and drink. The injunction is modified in respect of domestic animals to the extent that they may be roped or even whipped occasionally but always mercifully with due consideration and without anger. |

|

3. Vegetarianism |

|

Except for allowing themselves a judicious use of one sensed life in the form of vegetables, Jains would not consciously take any life for food or sport. As a community they are strict vegetarians, consuming neither meat, fish nor eggs, They confine themselves to vegetable and milk products |

|

4. Self restraint and the avoidance of waste |

|

BY taking the basic vows, the Jain laity endeavour to live a life of moderation and restraint and to practise a measure of abstinence and austerity. They must not procreate indiscriminately lest they overburden the universe and its resources. Regular periods of fasting for self-purification are encouraged. |

|

In their

use of the earth’s resources Jains take their cue from |

|

5. Charity |

|

Accumulation of possessions and enjoyment for personal ends should be minimised. Giving charitable donations and one’s time for community projects generously is a part of a Jain householder’s obligations. That explains why the Jain temples and pilgrimage centres are well endowed and well managed. It is this sense of social obligation born out of’ religious teachings that has led the Jains to found and maintain innumerable schools, colleges, hospitals, clinics, lodging houses, hostels, orphanages, relief and rehabilitation camps for the handicapped, old, sick and disadvantaged as well as hospitals for ailing birds and animals. Wealthy individuals are advised to recognise that beyond a certain point their wealth is superfluous to their needs and that they should manage the surplus as trustees for social benefit. |

|

The five fundamental teachings of Jainism and the five fold Jain code of conduct outlined in this Declaration are deeply rooted in its living ethos in unbroken continuity across the centuries. They offer the world today a time tested anchor of moral imperatives and a viable route plan for humanity’s common pilgrimage for holistic environmental protection, peace and harmony in the universe. |

|

* |

|

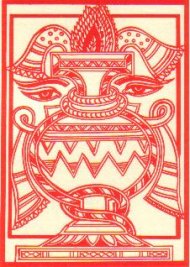

One of the eight Jain auspicious symbols (Ashtamangalas), the ‘Kumbh’.Any human venture would be commenced only after the ceremonial prayers of the ashtmangalas.The two eyes on the kumbh represent right knowledge and right faith. |

|

|

|

|

A JAIN PERSPECTIVE |

|

I am a Jain by culture, a word which few can spell. Even fewer have heard about Jainism, one of the oldest living religions of the world. I therefore belong to a minority group. As Indians are a minority, I am a minority within a minority. I have been living in this country for 25 years and have certainly encountered some prejudice. Visually, my complexion is black so I would stand out as different. Fortunately, affirming diversity is in my DNA, and as an Indian and a Jain, I have been brought up with an open mind and respect for other peoples, cultures and all living beings. |

|

Biodiversity is not a separate issue |

|

Jainism does not restrict diversity to humanity, but sees the entire ecosystem as diverse and all living beings as being worthy of equal respect. Human beings are just one of the species on the planet, and as we are on the top of the pyramid, we have a lot of power. But instead of using and abusing this power, Jains believe we have the greatest responsibility and accountability to other living beings. These are the values on which I was raised, and as a result, I feel they have given me a huge reservoir of strength in contributing to our understanding and practice of diversity in British society. My culture has taught me to seek wisdom wherever it may lie, and respect others despite their size, status or origins. Every living being is worthy of the highest |

|

respect. The sun never discriminates as to whom it shines its light on, so why should we? Jains take care not to harm even the smallest insects. We are all children of this vast planet, and there is room for us all. From a very young age, my family has taught me the highest level of integrity and humility. In fact, I have been taught to practise what I preach, so that my actions are synonymous with the things I write and say. |

|

In truth, we are all different – no two people are exactly the same – we know this from our own families, let alone the outside world. It is a question of degree. Even we ourselves change over time and are different from one year to the next. Thus diversity is an individually experienced reality, not a choice or an 'issue'. How we choose to accept it and live with it is what this book is about. The most important barrier to valuing and accepting diversity is the mind, and this is also the most important resource for change and transformation. Later in this book, we will look at how we can cultivate and nourish open-mindedness*. |

|

Learning from Kids |

|

Children are generally much more open-minded than adults. For very young children diversity is no big issue –they just want to play or paint or create with whoever is around them. Provided their actions and judgements are not influenced by adults or media, and they are exposed to different cultures, they can grow up quite broadminded. I have made many friends from different backgrounds through my children. Their friendships encourage us to get to know one another. We recently had a dinner party at home with some 'English' friends and our son reminded us quite casually that if it weren't for him, we wouldn't have made these new friends! |

|

Atul K Shah |

|

*Taken from his book “Celebrating Diversity” |

|

Published by Kevin Mayhew Ltd. Buxhall, Suffolk |

|

|

|

|

WHO AM I? |

|

My name meaning eyes. |

|

My roots background — Father House of Mewor |

|

Mother House of Travencore |

|

Father Aryan, Digamber Jain |

|

Mother Dravidian, Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Christian |

|

Both Indian origin so am I and the religion of the family |

|

(that includes me) are both. |

|

By root I am Aryan. |

|

Religion is not questioned but accepted. no question has an answer |

|

it can have many or no answers. |

|

I was born into two religions and thus I follow both. |

|

I am currently a tutor for SIFRE for both faiths and a student at UCS in BSc(Hons) S.E. |

|

My future ambition is to study a masters in S.E. or Internet Studies |

|

Working for SIFRE gives the feeling of being a valued member of the local community. |

|

If I do leave Ipswich (because my course is not offered here) |

|

then I would like to carry on the same kind of work in other IFREs. |

|

My name means eyes, |

|

My favourite sport is swimming, |

|

I am a whiz with computers tho' not a geek! |

|

I like to eat pizzas and no, I am not one. |

|

But I am an excellent disaster in the kitchen. |

|

T.V. is my addiction, so is sleeping |

|

- that's only when I am at home |

|

At college I study hard, work hard, and thus get a chance to relax when at home. |

|

My career is my ambition, |

|

I guess that makes me a career-minded person. |

|

What else can I say, get to know me and I will say |

|

Who am I? |

|

Nayan Shah (ex student) |

|

|